Why to be a Techno-Optimist

Throughout history, progress has improved people’s lives. With our best efforts, we can still be optimistic about the future.

Published

Published

In his Techno-Optimist Manifesto VC GOAT Marc Andreessen lays out a vision of a future where technology solves humanity’s problems and creates a world of infinite abundance. He thus takes a stand against the growing skepticism in the Western world towards technology and its blessings. As a tech company, we share much of Andreessen’s view on technology—and would like to add our more European perspective.

When your loved ones drink water, how often do you worry they will die of cholera?

Probably never, right?

Until 1990 almost a quarter of the world’s population lacked access to clean and safe drinking water. So, they feared the next drink of water could kill their child. And hygiene is only the tip of the iceberg: Without access to clean drinking water, sick children cannot make it to school. In many of the affected cultures, it’s women and girls who carry water home from the wells, not men. Something that has hindered them from going to work or getting an education.

Now, instead of 1 in 4 people living with this obvious problem, it’s 1 in 14. Over the course of 30 years, technological development has helped more people to get access to drinking water—and in 30 more, such problems will hopefully be a thing of the past.

Likewise, the number of people living in extreme poverty has dropped significantly in the past 30 years. In the 1990s there were 2 billion people living under the International Poverty Line (i.e., with a budget of less than $2.15 per day). Until now, the overall poverty numbers dropped by 35% to 702 million people affected.

That shows rapid progress is attainable, as the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) states. India, says UNDP, saw a remarkable reduction in poverty: Within a span of 15 years, 415 million people were lifted out of poverty. The same applies for countries like China and Indonesia. Meanwhile the global literacy rate among 15-year-olds and the overall life expectancy around the world has increased wherever there is access to technology and wealth.

Update: In this video, the late Hans Rosling, renowned Swedish physician and academic, demonstrates (in his inimitable style) the remarkable progress achieved since the Industrial Revolution.

This shows us that technology does create prosperity for mostly everyone—and not just for Silicon Valley billionaires. Based on World Bank statistics, the worldwide Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has increased ninefold since 1980, net, i.e., after inflation. This was also made possible through technological advances; the Internet gave us the ability to communicate, connect and create faster than ever before.

Countries and regions, even entire continents, have benefited tremendously from this development, driven by technological progress: On the African continent, life expectancy rose by nearly 10 years between 2000 and 2019, from 46 to 56 years, according to the World Health Organization. China is one of the two largest countries in the world; it also used to be one of the poorest. In 2021 China declared that it has eradicated extreme poverty, at least according to the national poverty threshold. Since 1978, it lifted 770 million people out of poverty. According to the World Bank, China has succeeded in building a “moderately prosperous society in all respects”. Outstanding regional developments in Chinese megacities such as Shanghai (pictured below) or Chongqing, Beijing and Guangzhou were only made possible by information infrastructure and technology, both accumulated in industrial and societal development.

Acknowledging these global developments and facts, it makes perfect sense that Marc Andreessen writes in his Techno-Optimist Manifesto:

Before founding venture capital monolith Andreessen Horowitz, startup investor and entrepreneur Marc Andreessen helped build the internet as we know it: He created Mosaic, the world’s first web browser with a graphical user interface, and founded Netscape. His impact after his achievements as founder and entrepreneur might have changed the world even more: Since he founded the VC goliath Andreessen Horrowitz (a16z), he has successfully financed various unicorn startups such as AirBnB, GitHub and Slack, and also invested in BioNTech (the German mRNA vaccine pioneers), Zoom and OpenAI—to name a handful.

Technology is a lever on the world; a way to make more with less. We believe that technology begets more technology at a constantly accelerating pace.

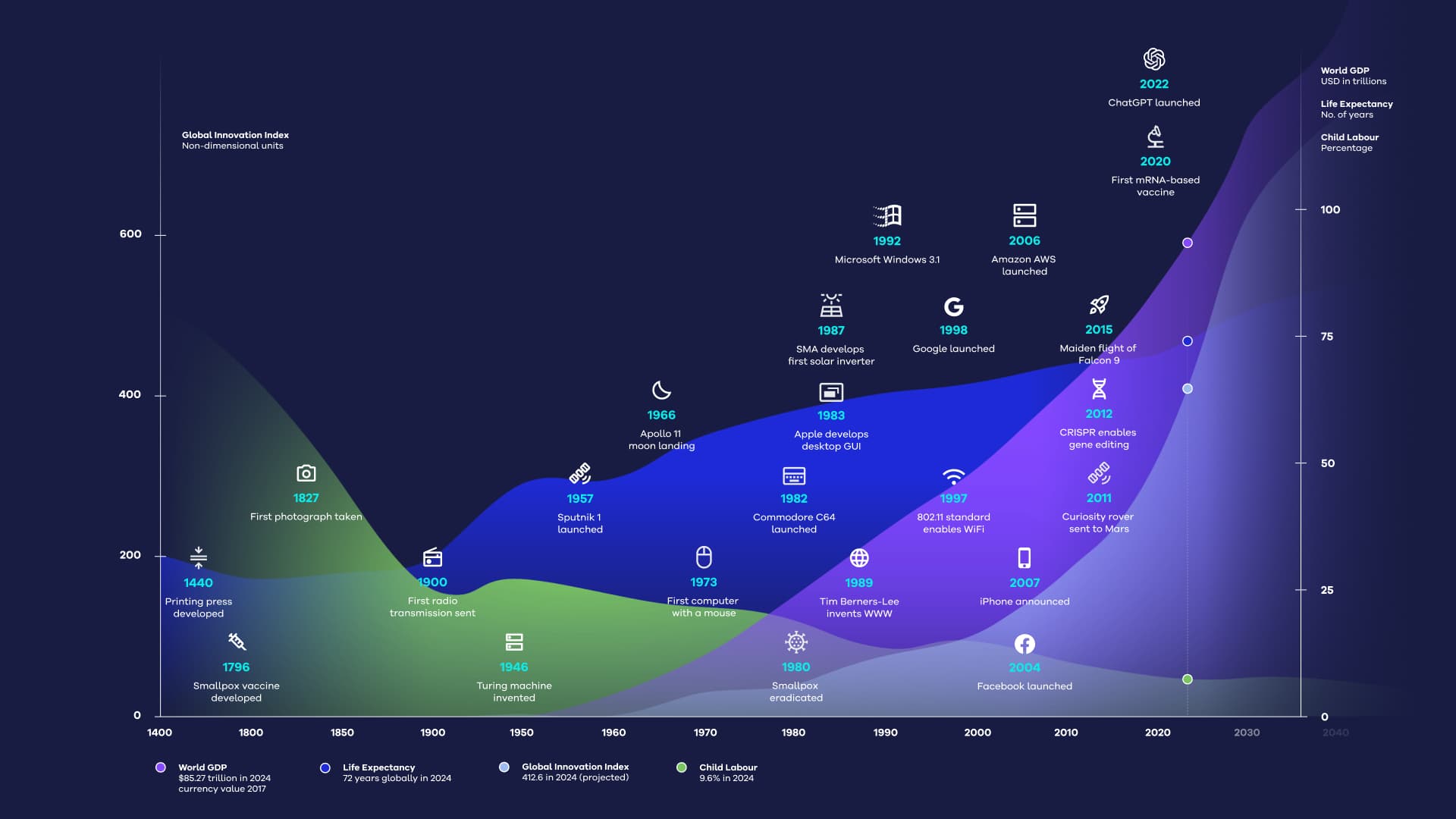

Update: This graph shows just a small selection of the significant technological advancements that have changed the world for the better including metrics such as the World's Gross Domestic Product (GDP), Global Life Expectancy, the Global Innovation Index and Child Labor.

This shows that technology is the key to achieving a better future for humankind.

By embracing advances instead of treating them with fear or skepticism, we can live in a world where Artificial Intelligence (AI) augments human intelligence, where clean water, reliable energy and acceptable healthcare are available to everyone and where freedom, security, and education are a given. Likely, there’s no other way to a sustainable and prosperous circular economy, no other cure for poverty, hunger, disease, and misery, than through technology. For example to help tackle air pollution, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) aims to research desirable technologies and solutions. According to UNEP, experts say, in the years to come, a digital ecosystem of data platforms will be crucial to helping the world understand and combat a host of environmental hazards. Without doubt, major structural transformations are inevitable to reach environmental sustainability, face climate change, and prevent pollution.

For Marc Andreessen, any problem facing humankind now or in the future, can and will be solved by technology. All achieved by driving technological progress forward with the optimism that things will work out in the end.

However, new technologies often receive a mixed welcome.

For example, the potential applications of Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) are astounding, especially in a world where climate change means we will need more resilient crops. But in a world where organic produce is prized, many are against genetically modified (GM) crops, which are seen as ‘unnatural’. Science has found that GM crops pose no greater risk to humans than other foods, but the European public remains unconvinced. “Many different types of modifications in various crops have been tested, and the studies have found no evidence that GMOs cause organ toxicity or other adverse health effects”, summarizes Megan L. Norris, cancer and developmental biologist and postdoctoral researcher at the University of Texas, in a blog post for Harvard Kenneth C. Griffin graduate school of arts and sciences.

And this raises the question: If we could feed more people with GM crops, reduce the spread of illness by modifying mosquitoes and eliminate genetic diseases, why shouldn’t we?

Andreessen states that by inhibiting or limiting technological development, we stifle innovation and—ultimately—harm humankind. If a technology could improve people’s lives and we refuse to use it or obstruct its use, then we are inflicting unnecessary suffering upon the world.

When dealing with new technologies, ethically, it might make sense to exercise caution if there may be unforeseen consequences. But should we not make decisions based on our current level of knowledge, and reevaluate when new information comes to light? After all, thanks to Copernicus most of us now agree that the earth revolves around the sun!

Is it right, then, to ban the use of CRISPR on crops, knowing people—including children—are starving today? Beyond crops, let’s consider the potential impact on wellbeing. If CRISPR can help with or prevent genetic disorders such as Down Syndrome, cystic fibrosis and AIDS, we should feel responsible to do whatever we reasonably can in terms of research so we can help affected families.

So, are ethical considerations holding us back, or is it fear? The latter often seems to masquerade as the former.

Likewise, developments in other fields such as autonomous vehicles, stem cell research and AI are slowed down by fearmongering and too much regulation too soon. Instead, we need as much regulation as necessary, and as little as possible. In all of these points, we agree with Marc Andreessen.

As companies and foundations race to develop Large Language Models (LLMs) and generative AI—with the hope (and fear) of attaining Artificial General Intelligence (AGI)—ever more warnings have entered public discourse with the aim of slowing or regulating AI development.

The European Parliament has proposed the AI Act, an entire regulation on (any) artificial intelligence—reaching from LLMs to potential applications:

The honorable goal of the European Parliament and the AI Act might be “to prevent harmful outcomes”, and yet it also caters to and deals with common fears and anxieties that often go along with revolutionary technologies. We don’t doubt the need to avoid ‘unacceptable risks’ such as cognitive behavioral manipulation or even an AI coup à la Skynet. Fair enough.

But in any reasonable society, it should be already in the best interests of the developers, researchers and scientists, as the AI inventors to mitigate those risks—and strive for mutually beneficial outcomes. The AI Act though, implements governmental supervision and tries to assess all AI systems they deem 'high risk'; any AI, model or application, that might pose high or “unacceptable” risks must go through a thorough evaluation. The length and rigor of such required assessments though, could have serious implications for the EU and its technological advancement in and through AI as a whole. AI creators may simply avoid developing and releasing their products and services in the EU, while EU-based AI developers may leave for greener pastures (as they often already do).

The risk is not just slowing Europe’s AI development but putting us out of the race entirely.

The question is therefore, how do we balance valid ethical standards with the required, responsible technical advancement?

In his Techno-Optimist Manifesto, Andreessen argues for a liberal approach, prioritizing tech above all else because the market naturally disciplines and regulates itself—and the market players. According to this idea, no state supervision, authority, or government, however well-intentioned, produces better long-term results than the market itself.

Since its publication, Andreessen's Techno-Optimist Manifesto has received much praise, but also a lot of criticism. In our point of view, to accuse Marc Andreessen and the advocates of techno-optimism of a lack of ethics or even unethical behavior per se is insincere. The mere fact that Marc Andreessen is very successful and has benefited from technological progress (which he has also helped to drive forward), even making him a billionaire, is no reason not to take a serious look at his point of view. It curtails the debate and does not do justice to his person. Moreover, it is certainly worth finding out the secret of his success, especially when he shares them so openly.

We therefore do not understand Andreessen's Techno-Optimist Manifesto to be a simplistic, “every man for himself.” Rather, we understand Andreessen in the well-meaning spirit of utilitarianism—or of Adam Smith himself, who drew our attention to the fact that every entrepreneur can only achieve long-term success if he serves the market, i.e., his customers and users—and thus, his fellow human beings. Nowhere is this more obvious than in Andreessen's famous venture capital firm: a16z surely invests its funds mostly in the startups and founders that focus on their customers’ and users’ interests and needs. Offering technology-based solutions for this (and them) is just the cherry on top.

Still, and even though we are very much in favor of this view, Andreessen leaves several aspects unaddressed. These include:

How do we deal with the accumulation of power, i.e., monopolies and oligopolies?

How do we deal with those affected the most by unavoidable market upheavals?

How do we deal with potential worst-case scenarios (if at all)?

Let’s take a closer look at this:

History shows that a libertarian, hands-off approach to free market economics results in monopolies that stifle innovation and hold society back. Driven through the economy of scale, successful businesses tend to grow bigger and bigger, accumulate increasingly more power over time up to a point where they keep away competitors not through lower prices and better innovations, but through power (e.g., through mergers & acquisitions). That’s why all modern, free societies have developed strong anti-trust authorities and laws. Having those regulatory frameworks in place has been incredibly beneficial in preventing monopolies that hinder free market economics more than benefiting them. Recent examples include the blocking of Adobe’s takeover of Figma, driven by EU and UK regulators because of concerns the merger would leave creatives with less (and thus in the long-run worse) choice than otherwise.

We assume that Andreessen is counting on the premise that even the strongest monopolies (including dictatorships) cannot remain stable in the long term—and we very much hope he is right. In fact, we ourselves tend to believe that no system can last forever if it goes against the interests of the people. But even assuming the premise is correct, the question arises: What happens to those who are affected by such monopolies (and dictatorships) for years and decades, sometimes even for generations?

Are we really supposed to stand still, bear it, and hope for better times?

That also leads us to our second point…

Without doubt, technological developments can result in far-reaching changes in society and the economy, and for the time being at least, not only positive ones. Market changes are often accompanied not only by uncertainties and volatilities, but also by hard consequences for those who get the short end of the stick. The history of capitalism is full of lessons in which thousands were affected by unemployment and poverty because market forces did not favor them. In the US automobile industry, increasing globalization and automation cost former workers—from Detroit to the Midwest—their livelihoods. Many lost their jobs, and some of them even lost their homes. They and their children were directly affected and felt the economic setbacks for decades. It was of little comfort to them to be told their industry will see better times again in the future. We cannot ignore that not only entrepreneurs and founders were affected by this, but also ordinary workers and citizens from educationally disadvantaged backgrounds. To impose the full brutality of market consequences on them, even if they themselves cannot fully comprehend them, is at the very least hard to bear.

The same applies to those less blessed by nature and society, who suffer from heart failure and, even with all the will in the world, will never be able to afford the cost of a new heart on a free market for organ trading. This also is hard to stomach.

In economics, this is referred to as possible market failure and market disruption.

Regarding market failure, we must also talk about potential Armageddon—or at least the fear of it.

Considering the latest breakthroughs in AI through tools like ChatGPT, based on LLMs, questions arise if this could ultimately lead to an AGI—and if so, how that would or could affect humanity. In early 2023, Elon Musk, Steve Wozniak and other thought leaders in the tech industry signed an open letter urging AI labs to pause training their systems for 6 months to allow space for better planning and management because AI could “represent a profound change in the history of life on Earth”. The Terminator depicts a vivid imagining of this scenario.

In a video from the annual DealBook Summit held by The New York Times, Elon Musk says he was losing sleep over the threat of AI danger, but a fatalistic resignation allowed him to sleep again. Because even if annihilation through AI was certain, he “probably would choose to be alive at that time because it’s the most interesting”. Even if there was nothing he could do about it.

AI is not the first potentially existential threat for humankind, and it won’t be the last. What would have happened if humanity had nuked its way out of the Cold War after the discovery of nuclear fission and the development of the atomic bomb?

It may be ethically honourable to believe in the goodness of humankind and to trust that everything will be fine at some point. But in view of potentially catastrophic risks, would it still be responsible to rely on faith alone?

It goes without saying that politicians, including governments, must address these market risks and the associated upheavals, as well as those affected by them. And we share the view that this should always be done according to the motto: As much intervention as necessary, as little as possible. That does not free us from the responsibility of being empathetic—and being mensch.

Update: In the middle of the 19th century with the forces of the Industrial Revolution in full effect for close to a century, certain industrialists undertook initiatives seeking to benefit their entire workforces and their families.

In 1861, Europe’s largest company at the time, Friedrich Krupp AG (now Thyssen Krupp AG), started the “Sozialwerk”, a social services program for its workforce. After discovering a lack of available housing for his workers, then CEO Alfred Krupp, had his firm build them somewhere to live. The so-called Margarethenhöhe still stands today in Essen, the second largest city in the “Ruhrgebiet”. Krupp’s program was further developed to include free employee medical services, for example. Later also technical and manual training schools were provided. And the firm contributed to and supported the accident, life, and sickness insurance societies that formed. As well as being Germany's premier weapons manufacturer during both world wars, after the Nazis seized power in Germany, Krupp supported the NS-dictatorship and was one of the many German businesses that profited from forced labor of foreign civilian workers, concentration camp prisoners and prisoners of war. Today, Thyssen Krupp AG faces headwinds from a challenging business environment and is undergoing a lengthy transformation.

Another industrial-age example comes from the UK. In 1888, the Lever Brothers (founders of Unilever) started building the village “Port Sunlight” exclusively to house their workers in the metropolitan area of Liverpool. They also introduced welfare schemes and provided for the education and entertainment of their workforce, encouraging recreation and organizations that promoted art, literature, science, or music.

Similarly, in 1893 the Cadbury brothers (of chocolate fame in the UK and now part of Mondelēz International) purchased 120 acres (or 0.5 square kilometers) of land close to their factory and built the village, Bournville. With it, they intended to "alleviate the evils of modern, more cramped living conditions" for their workers. Unlike many industrialists of the time, they had a deep-seated concern about the way so many had to work and live in overcrowded, dirty and dangerous places. Alongside housing, extensive space and facilities were provided for enjoyment by Cadbury employees.

Having the conviction to ensure the workforce has secure accommodation and providing them with a range of facilities and services for their health and enjoyment was revolutionary in the late 19th century. It’s fair to say that this was and still is a visionary approach to how to operate a business and be a mensch—at least at the given time or in the given circumstances.

We believe, and it might be a European perspective, technological advancement and free markets need checks and balances—otherwise they could lead to a dystopia. As Yuval Noah Harari writes in his book Sapiens:

While Harari has a more cautious or pessimistic view of technology than us, we agree it’s not enough to strive for more and faster material, technological developments alone. Instead, to ensure technological progress moves in the right direction, we must also continue to develop as individuals and societies. In short: we have got to evolve, too.

Maybe, there is no one size fits all. Maybe, this is also about the market of regulative ideas. So, instead of a global ruleset, each new technology can be considered by each jurisdiction on its own merits—based on the local optimum, which can be defined as a point in a problem space that is better than its immediate neighboring points. Maybe looking beyond those jurisdictions will then lead us to other, newer, and better ideas. And maybe there is no “best” solution. Maybe progress is also required through regulative developments. As much as regulations are opposed by libertarians, we may have to take the time to go through the process of trial & error to work and evolve in those developments. In the end, we believe that the technological advancements of the 17th to 19th century required not only technology, but also the Renaissance. We also share Andreessen’s fear of facing a time of anti-enlightenment, one in which not only technological but also social progress is met with reluctance and skepticism—or even open hostility.

Unlike Harari, we do not fear AI leading to a ‘useless class’ in society with no economic, military or political power. Instead, technology and AI will broaden the horizons of what is possible for human beings. Or as Marc Andreessen puts it:

And where we agree, even if we believe that regulation is needed: The sweet spot seems to be, as much morality as necessary, but as little as possible.

We agree with Andreessen that the goal is not to create a utopia, but to get as close as possible. We explicitly encourage anything to help us do the best we can with what we have—to lift humankind up so we can each become the best version of ourselves.

In that sense, we are also Techno-Optimists.

That’s why we’d like to take the opportunity to share our very own Yatta Manifesto with you: To show you what moves us and why we are here.

Share

See all